Today I’m sharing the different ways financial advisors charge for their services.

In fact, there are FOUR main fee structures you might come across when interviewing advisors…

…and each one can be a disservice to someone.

In this episode, I’m covering three important things:

Key Takeaways

- What are the four fee structures and their pros & cons

- Who is (and isn’t) a good fit for each service model

- How much do financial advisors typically charge for their services

I’m also sharing how retirement savers might think about measuring the value of financial advice.

If you’re ready for a deep dive into financial advisor fees, you’re going to enjoy today’s episode.

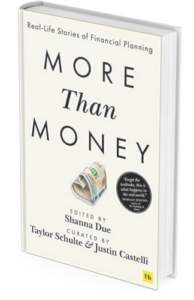

More Than Money – Last Chance!

Do you want to support my upcoming book and help improve financial literacy?

If so, I’m extending my “buy one, give one” campaign through the end of January 2023.

Here’s how it works 👇

- Pre-order a copy of More Than Money (Kindle or physical copy) before Jan 31.

- Email a screenshot of your order to book@youstaywealthy.com.

- I will personally match your order and send you a second copy to gift to someone in your life.

Once again, nobody is making a single dollar from this book, and 100% of the net proceeds are being donated back to non-profit organizations like the Foundation for Financial Planning.

Thank you in advance for your support!

~Taylor

How to Listen to Today’s Episode

🎤 Click to Listen via Your Favorite Podcast App

Episode Resources

- Subscribe to the Stay Wealthy Newsletter! 📬

- More Than Money: Real Life Stories of Financial Planning

- Financial Advisor Series [Stay Wealthy]:

- Robo Advisor Series [Stay Wealthy]:

- Financial Advisor Fee Trends [Kitces 2020 Study]

- Letter Your Broker Won’t Sign [Stay Wealthy]