Today I’m kicking off a two-part series on Small Cap Value investing.

Specifically, I’m addressing three big questions:

- What exactly are small-cap value stocks?

- Why have small-cap value stocks, historically, outperformed most major asset classes?

- Does the recent 20-year underperformance suggest that the strategy is dead and won’t work in the future?

I’m also sharing critical differences between small-cap value funds + how to take action if you want to include this asset class in your portfolio.

Listen To This Episode On:

When You’re Ready, Here Are 3 Ways I Can Help You:

- Get Your FREE Retirement & Tax Analysis. Learn how to improve retirement success + lower taxes.

- Listen to the Stay Wealthy Retirement Show. An Apple Top 50 investing podcast.

- Check Out the Retirement Podcast Network. A safe place to get accurate information.

+ Episode Resources

- Stay Wealthy Episodes Referenced:

- Rubin Miller

- Value Investing

- Is Systematic Value Investing Dead? [AQR]

- It’s Too Soon to Say the Value Premium Is Dead [Morningstar]

- Value Is Dead, Long Live Value [OSAM]

- Small Cap Stocks

- What Are Small Cap Stocks [Investopedia]

- Avantis U.S. Small Cap Value [Avantis]

Performance data shown represents past performance. Past performance is no guarantee of future results and current performance may be higher or lower than the performance shown. The investment return and principal value of an investment will fluctuate so that an investor’s shares, when redeemed, may be worth more or less than their original cost. Average annual total returns include reinvestment of dividends and capital gains. To obtain Dimensional Fund performance data current to the most recent month-end access our website at www.dimensional.com. See Standardized Performance Data and Disclosures. Performance for periods greater than one year are annualized unless specified otherwise. Indices are not available for direct investment; therefore, their performance does not reflect the expenses associate with the management of an actual portfolio. Prior to listing date the following ETFs operated as mutual funds: DFUS, DFAC, DFAS, DFAT listing date 6/14/21; DFAX, DFIV listing date 9/13/21; and DFUV listing date 5/9/22. The NAVs of the predecessor mutual funds are used for both NAV and market price performance from inception to listing.

+ Episode Transcript

Small Cap Value Investing (Part 1): Is This Popular Strategy Dead?

This show is a proud member of the Retirement Podcast Network.

Taylor Schulte: Welcome to the Stay Wealthy Podcast.

I’m your host, Taylor Schulte, and today I’m kicking off a two-part series on small-cap investing. In this series, I’ll be addressing three big questions.

Number one, what exactly are small-cap value stocks?

Number two, why have small-cap value stocks had higher long-term returns than most other major asset classes?

And finally, number three, does the recent 20-year underperformance of this asset class suggest that the strategy is dead and won’t work in the future?

I’m also sharing critical differences between small-cap value funds investors can own and how to take action if you want to include this asset class in your portfolio.

To view the research and articles referenced in today’s episode, just head over to youstaywealthy.com/225.

Small-cap value stocks are known to contain more risk than large-cap stocks. Investors willing to take this extra risk, they do so with the expectation that they will achieve higher returns.

However, since 2004, the S&P 500, an index comprised of the 500 largest US stocks, the S&P 500 has outperformed small-cap value stocks by over 100%. Two entire decades of underperformance. Before we explore this asset class any further and dissect this recent 20-year time period, let’s quickly revisit the four primary drivers of equity investing returns.

Number one, the market.

Number two, company size.

Number three, relative price.

And finally, number four, profitability.

The first driver, the market, is pretty straightforward. In short, the stock market is riskier than the bond market. For that reason, investors should expect higher returns from stocks than bonds. And that’s exactly what they’ve experienced over long periods of time. In the academic investing community, this is known as the equity premium. You get a premium or some extra return for taking risk and investing money in stocks.

The second driver, company size, is also pretty straightforward. Small companies are riskier than large companies. So if an investor takes more risk by investing in smaller companies, they should expect a higher rate of return. And that’s exactly what small-cap investors have experienced. And this should make intuitive sense. You wouldn’t invest in a no-name biotech company on the brink of a world-changing discovery just to earn the same boring return as a company like Apple or AT&T.

The third driver is relative price, and we’ll be digging into this more shortly. But in short, stocks that are trading at lower relative prices, i.e. value stocks, have higher expected returns and have had higher historical returns than stocks trading at higher relative prices, i.e. growth stocks.

And then lastly, the fourth driver is profitability. This driver gets a little nerdier, so I’ll just keep it simple by sharing that the profitability driver or profitability premium concludes that stocks with high relative operating profits have higher expected returns than companies with lower relative operating profits.

So what does all this mean?

Well, while we don’t have a crystal ball, evidence suggests that investors do have some control over their future long-term returns. Specifically, these four drivers represent four decisions that an investor can make to put themselves in the best position for investment success.

They can allocate more to stocks than bonds, more to value stocks than growth stocks, more to small-cap stocks than large-cap, and more to companies with high relative operating profits. And to be extra clear, I’m not suggesting that an investor should put 100% of their portfolio in high profitability small-cap value stocks.

As we are all too familiar with at the moment, even some of the best asset classes in the world can underperform for long periods of time. Diversification is important, but if an investor wants to improve their future expected returns, overweighing one or more of these four drivers in their portfolio is a decision for them to consider making, a decision that they have control over.

That being said, if an investor used this research to use these four drivers of returns 20-years ago to guide the construction of their portfolio, they’re likely scratching their head right now, wondering why things did not play out as expected.

Why have riskier small-cap value stocks underperformed plain vanilla large-cap stocks for the last two decades? And does this change how investors might think about investing in this asset class and using these four drivers to make portfolio decisions going forward?

Before we address those very good questions head on, let’s first define what small-cap value stocks are. And let’s start by pushing the word value to the side for a moment.

What exactly is a small-cap stock? While figures and opinions will vary a little bit, a small-cap stock is generally a company whose total market value is between $250 million and $2 billion.

And to prevent any confusion here, total market value is just another term for market capitalization, or market cap for short, which explains the use of the word cap in small-cap. So small companies generally have a market cap between $250 million and $2 billion.

To calculate a company’s market capitalization and determine if it’s a small-cap, mid cap, or large-cap company, you would simply multiply the current share price of its stock by the number of outstanding shares.

For example, Apple currently has around 15 billion outstanding shares. Outstanding shares are just shares owned by institutions and investors across the world and exclude shares that the company owns itself. So if you own some Apple stock in your portfolio, your ownership stake is part of the 15 billion shares outstanding. So Apple currently has around 15 billion shares outstanding. And as of this episode, Apple’s stock is trading around $220 per share.

So we would multiply 15 billion by $220 and arrive at a total market value or market cap of around $3.3 trillion. This makes Apple as of today, the most valuable company in the world and very, very, very far away from being categorized as a small-cap stock.

Now, while the size of a company is fairly easy to figure out, the definition of a value stock can be more subjective. And that’s mostly because there are many different methods that one can use to conduct their analysis and determine if a stock is a value stock or a growth stock. At a very high level, value stocks are companies with share prices that are lower than what their fundamentals suggest that they should be.

For example, an analysis might lead an investor to conclude that XYZ stock should be trading at $50 per share, but right now it’s currently trading at $40 per share. Its share price is $10 lower than what the fundamentals suggest. The market is undervaluing or underpricing the company.

In this example, a value investor would buy this company and others with similar characteristics at what they’ve determined to be bargain prices, and then they would hold them for long periods of time.

Putting this all together, a small-cap value investor or small-cap value fund would look to buy small companies that appear to be undervalued and trading at a discounted price. One of the popular small-cap value fund managers, Avantis, describes their fund’s objective as follows.

The Avantis small-cap value fund invests in a broad set of US small-cap companies and is designed to increase expected returns by focusing on firms that are trading at what we believe are low valuations with higher profitability ratios.

So why exactly does a company like Avantis or any other small-cap value investor or fund manager, why do they believe so strongly that this sort of approach increases expected returns?

Well, to answer this, let’s once again break this asset class apart and set the word value to the side for a moment. We already know what a small-cap stock is. It’s a small company and smaller companies are riskier. As I’ve emphasized many times here on the show, if you take more risk as an investor, you would or should expect a higher return.

It’s really not all that different than lending money to someone. If your long lost cousin who just got his first job and doesn’t have any credit history asks to borrow money from you, you’ll probably charge him a higher interest rate on that loan than let’s say your best friend with an 800 plus credit score and a healthy six figure income. If you take more risk with your money, you should expect a higher rate of return.

So yes, small-cap stocks are riskier and in turn over long periods of time, these riskier small-cap stocks have significantly outperformed their more stable large-cap competitors.

Now, what about value stocks? Why would value stocks have higher expected returns? Well, as noted earlier, a value investor aims to buy struggling or unloved companies that have long term potential at what they have determined to be a bargain price. If they’re patient and disciplined, and their analysis proves to be correct, they should experience higher returns than an investor who bought a stock that was fairly valued or even overvalued.

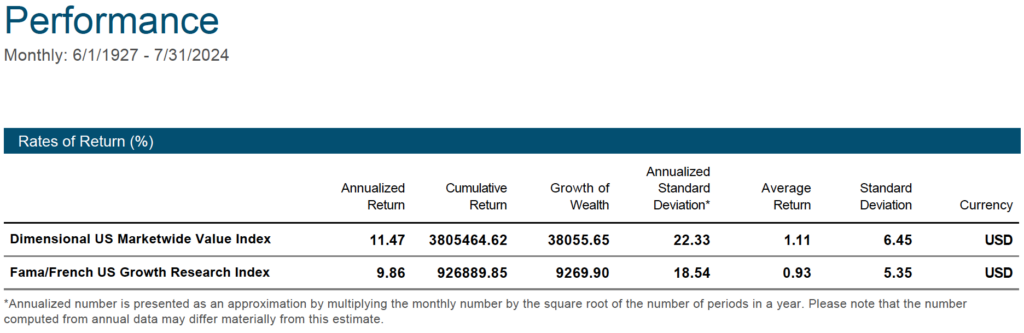

Value investors are taking some extra risk to buy an unloved company or a basket of unloved companies, and in turn, over long periods of time, are rewarded for taking that risk. To put some numbers to this, from June of 1927 to July of 2024, US value stocks have outperformed US growth stocks by almost 2% per year on average.

Now, that doesn’t sound like much at first, but we can’t forget how magical compounding is. If you invested $1 in the dimensional US market-wide value index in 1927, that $1 would have grown to $38,000 today. On the other hand, $1 invested in the dimensional US growth index would only be worth roughly $9,000. A 2% per year outperformance starts to make a significant difference over long periods of time.

Since we now know that small-cap stocks are riskier than large-cap stocks, and value stocks have historically provided a premium for investors willing to buy them when they’re unloved and trading at a discount, we should then expect that small-cap stocks with value characteristics, i.e. small-cap value stocks, we should then expect that small-cap value stocks should have even higher expected returns than just all the small-cap stocks across the board.

And that’s exactly what we’ve experienced over long periods of time. According to data from DFA Returns, since June of 1927, small-cap value stocks have had an average annual return of just over 13%. While all US small-cap stocks across the board, growth and value have had an average annual rate of return of 12%.

I’ll be diving deeper into the long-term historical performance of different asset classes in part two of this series. But first, with small-cap value stocks underperforming the S&P 500 for the last two decades, many investors have been questioning and debating if this strategy is dead.

In other words, does the small-cap value premium still exist? Are the popular accounting measures used by investors to measure value? Are they not capturing the fact that we are now living in an era where a handful of global winners dominate the markets, i.e. the Magnificent Seven?

With information so accessible these days, are too many people now aware of the strategy for it to work going forward? If everyone is buying these bargain price stocks, have the bargains simply been eliminated?

I’ll provide some compelling answers and rebuttals to this question in the show notes, but I think my good friend Rubin Miller summed it up really nicely when he last joined me on the show. Here’s a clip of him sharing why he thinks the value premium will continue to persist.

Rubin Miller: They call them relatively low price companies because people don’t really want to own them. They’re not that exciting and whatnot. And the way investors just think about this is not to pull out the Finance 101 book or with a bunch of equations.

But just think about in a rational world, if you have the option, I’ll use McDonald’s as a kind of established player and then a non-established player.

So, let’s use some, you know, the restaurant down the street. It doesn’t have to be a publicly traded company. Just take a McDonald’s franchise and some restaurant down the street that you like. And if I told you you’re going to get 10% a year return, you already know that, you’re going to get 10% a year.

Which company are you more excited about holding that year? You’re going to have a leadership in it. Which one do you want to own? Most people would say, well, I’m more comfortable with McDonald’s. It’s more robust. It knows how to make money. It’s more profitable. It’s got more resources and all that. And if I’m going to get the same 10%, I’ll just take the easy way out, you know, the less risky one.

And that’s how you should think about value and growth stocks, which is that people tend to want to own these nice solid companies. And so, how is the market going to incentivize people to own less nice companies?

And that’s the story, which is that’s what the value companies are. They’re less nice companies, but every stock has to be owned. And so, the way that the market has traditionally done this is that there is a premium to own value stocks.

Depending how you measure it, it’s about 2% to 3% a year, but like stocks, it’s very volatile itself. Many years growth does better than value, but on average, value does better than growth about 2% to 3% a year. And that’s why owning the kind of crappy companies in the market.

But it has to be that way. It has to be that way because every stock has to be owned. And so how do you incentivize people to buy less nice companies? You have to give them a slightly higher expected return. And we’ve realized that higher expected return in the last hundred years.

There’s no reason to think going forward that all of a sudden, everyone’s going to want to own crappy companies. I don’t think that’s the case. I think people are always want to own the nice companies that have cool outlooks and sound cool and have all smart people working there.

And so, that means the prices of these value stocks are essentially, you want to think about as being somewhat depressed for what they’re offering. And I have no reason to think value stocks wouldn’t do better than growth stocks going forward. The caveat as asset allocators is I don’t know when that’s going to show up.

So similar to the way you and I say, I don’t know what stocks are going to be next year. I have no idea if value is going to be growth or growth is going to be value. I just expect over really long periods for value to do a little bit better because I just can’t imagine a world where people get to buy kind of the nicest, shiniest companies and get the highest returns.

That doesn’t make sense to me. Otherwise, no one’s going to own the other stuff.

Taylor Schulte: I love the way he frames it up there at the end. How do you incentivize people to buy less nice companies? Well, you give them a slightly higher expected return. There’s no reason to think that going forward, all of a sudden, everyone’s going to get excited about owning crappy or unloved companies. People are always going to want to own the innovative companies that tell a good story and sound cool and have all the smart people working there.

That last part kind of reminds me of the famous Warren Buffett quote that says, “the stock market is the only place where things go on sale and everyone runs out of the store.”

Rubin’s comments there also helps to bring the risk of value investing to the surface. You know, with small-cap stocks, it’s almost easier to see and feel and understand the risk. These smaller companies are simply more volatile day to day, month over month, than larger, more stable companies. And that’s to be expected when we invest in smaller, less known companies.

But value companies aren’t necessarily more volatile or risky than growth stocks day to day. The real risk of value investing is that investors don’t know exactly when the value premium will show up or how long they need to hold their value stocks in order to reap the benefits. Successful value investors have to one, understand and believe in the philosophy. Remember, the best investment is the one you can stick with.

And two, value investors need to be incredibly patient and disciplined. So back to the initial questions that led us here. Why have riskier small-cap value stocks underperformed plain vanilla large-cap stocks for the last two decades?

And while Rubin makes a compelling argument, does or should the recent underperformance change how investors might think about investing in this asset class and using the four drivers of returns to make their portfolio decisions going forward?

In addition to answering these questions next week in part two, I’m also going to be sharing why not all small-cap value funds are equal and how investors might consider implementing this asset class in their portfolio if they determine that it’s fitting.

In addition, I’ll share why small-cap value investing might actually be less risky than investing in just the plain vanilla S&P 500 index.

Once again, to view the research and articles supporting today’s episode, just head over to youstaywealthy.com/225.

Thank you, as always, for listening and I’ll see you back here next week.

Episode Disclaimer: This podcast is for informational and entertainment purposes only and should not be relied upon as a basis for investment decisions. This podcast is not engaged in rendering legal, financial, or other professional services.